A large proportion of cases in gynaecology, urology, general surgery and orthopaedics are done today with small incisions: why has this trend not caught on in cardiac surgery in the UK? In the late 1990s there was much interest from many Cardiac Surgery centres in the UK, and across Europe to start minimally invasive programs. Many centres started and stopped, due to poor outcomes. Two groups, one based in Aalst, Belgium, led by Hugo Vanerman and another in Leipzig, Germany, led by Fredrich Mohr persisted in using the available technology for minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. Both groups published large series of over a thousand patients each by the early part of this century and this has then led to a gradual re-adoption of this technology, once more, across Europe. Over the past 10 years, the proportion of mitral valve procedures done through a key hole approach in Germany and Belgium has risen to near 60%. In most centres that offer a keyhole approach, the percentage of cases done are close to 90%. Sadly in the UK, less than 5% of mitral surgery cases are presently done by a keyhole approach. There are very good reasons for this big disparity, that may become obvious if I recount our learning process in Blackpool.

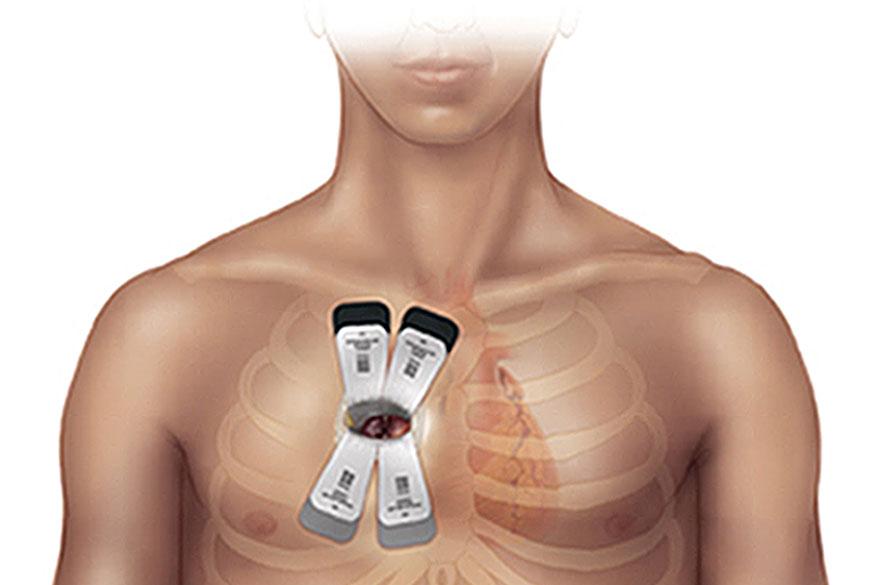

We started this program in 2007 at the Lancashire Cardiac Centre. Having looked at the different techniques, we decided on using the Endoclamp to build our experience. The Endoclamp is patented by Edwards Lifesciences, and has a cost associated with each use. The Endoclamp is a clever idea that helps isolate the heart and is used to deliver a high potassium solution to still the heart, so that the surgeon can work on fixing the defect in the valve. The advantage of going with the Endoclamp, is that the company funds the surgeon and the team, to visit an established centre for a training course and then brings a paid proctor to watch over the first few cases done. The first hurdle we faced was to convince the hospital authorities that a new procedure needs to be introduced. Previous experience of this procedure and its poor safety record lead to much anxiety. The reasons for past failure needed to be understood to move on. In the late 90s the technology available for Thoracoscopes were very basic. As technology got better, the light source and the definition of the picture on the screen improved greatly. The magnification of the valve is 5 times the real size and with high definition screens and cameras the detail that is visualised is actually better than is seen by the naked eye. The introduction of 3 dimensional thoracoscopy is going to be a further enabler in applying this technology to a wider group of patients. Another great advance has been the routine use of Trans Oesophageal Echocardiography (TOE) by cardiac anaesthetists. They are able to give real time pictures of the position of the different cannula, the inflation of the Endoclamp, the success of the procedure and at the end, the function of the heart. I do believe that with better thoracoscopes and routine TOE, minimally invasive mitral surgery has become safer. We were fortunate to have new Video stacks and all our anaesthetic colleagues were trained to provide TOE during surgery. This was a big help in setting up our program safely. So once the Governance team was convinced, that we had learnt lessons from the past and were confident that we will have comparable results with the small incisions, we then had to convince the finance managers that this will save costs in the long run. This is very hard in the NHS, where not even the finance managers really know exactly how much a day in hospital costs! We made the case that, patients with smaller incisions would spend less time in both intensive care and on the ward. We also hoped that the blood transfusion and infection rates will be lower, and all this would even out the expense of the Endoclamp and other single use instruments required for this type of procedure. Once we had got clearance to start the program, we faced the huge pressure of offering this procedure without a learning curve. As the results of mitral surgery through a sternotomy are so good in the UK, improving on it is no easy task on a background of higher expectations from both patients and payers.

We at Blackpool began, after visiting Aalst and Middlesborough, where the teams had started before us. To date we have done over 200 cases using a small right sided mini thoracotomy, offering it to patients needing surgery on the Mitral and Tricuspid valve. We also offer it to patients with an Atrial septal defect (hole in the heart) and those with atrial fibrillation (irregular heart rhythm). The advantages we found were, apart from the obvious cosmetic benefit to the patient, we have noted that less than 5% of our patients have required a blood transfusion compared to an 18% blood transfusion of cases done with a sternotomy at our institution during the same time-frame. We also noted that patients seemed to go home at least a day or two earlier and have had very few patients affected by infections. The results are even more striking when patients come for a second or third heart valve procedure. The biggest advantage that patients tell us regularly, is how quickly they get back to what they consider normal life. We did find some disadvantages too. The procedure takes longer. It costs more up front. The other concern is that blood has to flow in the opposite direction in the body and so the risk of having a small particle floating to the brain and causing a dreaded stroke is higher. We learnt early that doing a routine CT scan on all patients and a pre operative TOE helped us to identify the group that were at a higher risk of a stroke. These patients are better served by sternotomy, until we have further technological advances. We have not had a stroke in a single patient in our series of isolated mitral valve procedures in the last 100 cases. However, we have had 5 patients who have died following the procedure, most of them highlighted as high risk. We have learnt from some of these deaths, and going forward we expect our results will be even better. Over the past five years, we have had teams from Glasgow, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, Newcastle, Sheffield and Denmark, visit us. The procedure is now offered in Middlesbrough, Basildon, Liverpool, Sheffield and Kings College London.

Today, the NHS is noted to be cash strapped and new procedures that require capital funding are not easy to introduce. Centres and surgeons who have had bad results in the past have often labelled this procedure as dangerous. These bad memories then make it harder to convince the governance team in a hospital to give the go ahead. Small incision cardiac surgery is not an easy procedure to learn quickly. Cardiac surgeons have often spent 20 years to get to a consultant job. With results being closely scrutinised, the incentive to start another learning curve is not high up on the priority list. Also, there are many different components to learn and the surgeon has to depend and communicate effectively with the whole team to do this safely. It is crucial that the team works together regularly, so that the learning curve is shortened. This is becoming increasingly difficult in the present NHS with nursing shifts and consultant job plans that don’t always closely match.

Despite all this, most people agree that the future of mitral surgery is through small incisions. There have been 8 UK consultant jobs advertised, requiring experience with minimally invasive mitral surgery in the past year. The challenge for the UK is to make sure that the wider dissemination of this is done safely. For a start, I do think every case attempted should be recorded, so that we can develop a registry that will teach us which patients will not benefit from a small incision. We need to transfer knowledge between centres with more experience to newer centres, by regular meetings and simulation courses. Commissioners need to recognise the advantages, and offer some incentive to the hospitals to adopt this. New technology that makes these procedures reproducible and safe needs to be funded. There will always be cases that will need a sternotomy: the hope is that the percentage of sternotomy cases will get fewer by the year. Keyhole surgery should not be seen as competitive technology, rather collaborative. There is no doubt that this type of surgery is not for all patients. We will find out over the coming years, if this kind of surgery is for all surgical teams. The responsibility on us surgeons is that patients should not end up losing out in the process.